Rise of the Umbrella

23 St James's Street

In 1838, just a decade following Thomas's establishment of his business, John Tallis released a pictorial plan of St James’s Street, outlining its various merchants.

Among them, number 23 was identified as Brigg - specialising in umbrellas, canes, and whips.

Umbrellas rose in prominence within the Brigg family business, reflecting their surge as essential waterproof accessories in British society. By 1898, Brigg had transformed from a small enterprise handling everyday umbrella repairs to a renowned brand crafting high-quality, distinctive umbrellas for aristocratic patrons at premium prices.

Throughout numerous civilisations worldwide, a portable personal canopy, often carried by attendants, served as a hallmark of secular or sacred status.

the Brigg Umbrella

Umbrellas doubled as sunshades, with their English names reflecting this origin: parasols shielding against the sun, while umbrellas (derived from Latin "umbra") providing shade. It was as sunshades that their adoption expanded across broader society, particularly among affluent women. By 1780, the umbrella had integrated into fashionable women's wardrobes, shielding their delicate complexions and aiding in flirtation.

By the mid-17th century, the French began producing their own parasols and coined a more suitable term for rain protection - the "parapluie". Around 1715, Monsieur Marius introduced a foldable parapluie advertised to fit conveniently into a pocket when not in use.

While "parasol" retained its meaning as a sunshade, "umbrella" became synonymous with rain protection, likely because the British easily associated shade with clouds.

Umbrellas faced slower acceptance in British society. While a woman with a parasol flaunted her fair skin and independence, carrying an umbrella implied reliance on foot travel during inclement weather, rather than the luxury of a sedan chair or carriage.

Adoption of Umbrellas in British Society

For a significant period, only doctors and clergymen were permitted umbrellas. Their proliferation became evident in the 1780s, appearing in court records as stolen items.

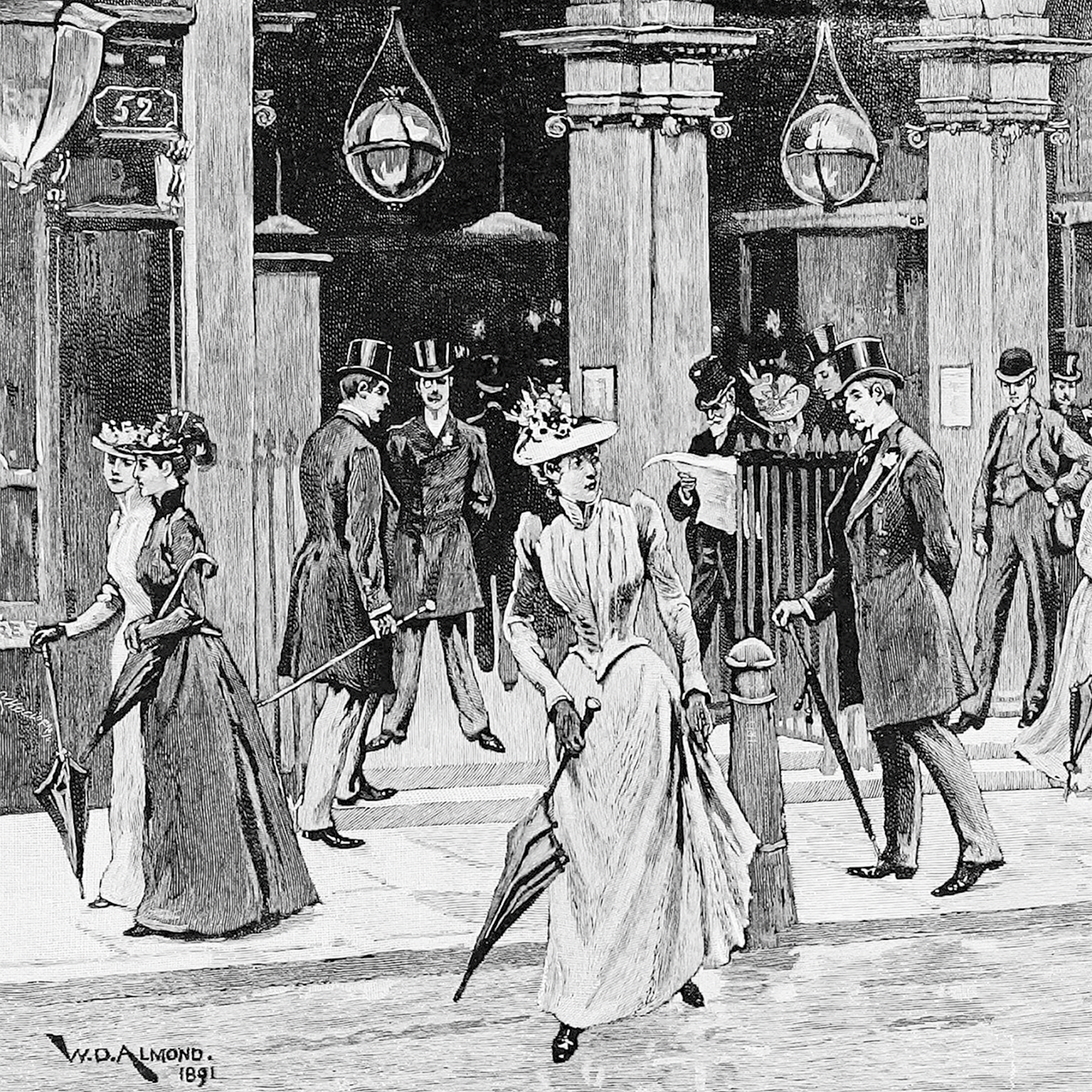

By the 1920s, satirists began exploiting their comedic potential, particularly regarding social status and manners.

Remarkably, within a generation, carrying an umbrella shifted from indicating a lack of covered transport to signalling freedom from burdens like shopping or work tools. Fast forward to the interwar period, and it became uncouth for a gentleman 'in town' to carry anything other than a neatly furled umbrella, highlighting the class distinctions in British society.

The adoption of umbrellas in Britain was facilitated by technological advancements, making them more practical and efficient. Early European examples featured wooden frames and painted leather covers, cumbersome and heavy, requiring servants to carry them. Introduction of whalebone or cane ribs and oil-proofed silk or cotton covers significantly reduced weight, enabling single-handed carriage.

These lighter alternatives were widely available in Britain by 1800, leading to a cottage industry of umbrella-makers who assembled frames and stitched covers. Charles and Thomas Brigg likely entered the industry at this level, as suggested by their advertisements in the 1820s.

Technological Advances with Umbrellas

In the 19th century, the introduction of steel ribs revolutionised umbrellas, making them lighter, sturdier, and slimmer. Among the leading manufacturers were Henry Holland of Birmingham and Samuel Fox of Stocksbridge.

In the 1980s, the sewing machine brought about another technological leap. While initially celebrated for speed, high-end producers like Brigg recognised the superiority of hand-sewn covers.

This tradition persisted until after World War II, when skilled seamstresses became scarce. Today, machine sewing is standard, but Brigg maintains the distinction of hand-cut gores and turned and stitched edges, setting their products apart from cheaper alternatives.

The Gentleman’s Umbrella

Following WWI, the walking stick's popularity declined, likely due to the rise of motoring and its association with mobility aids for war veterans. Fortunately for Brigg, this decline coincided with the umbrella's ascent as a gentleman's accessory.

By the 1930s, a professional man without a furled umbrella was unthinkable in London, making it a walking stick in all but name.

To commemorate this shift, Brigg introduced the ultra-slim "Centenary" gentleman's umbrella.