Article: The Great Days of the Silk Hat

The Great Days of the Silk Hat

A Historical Account

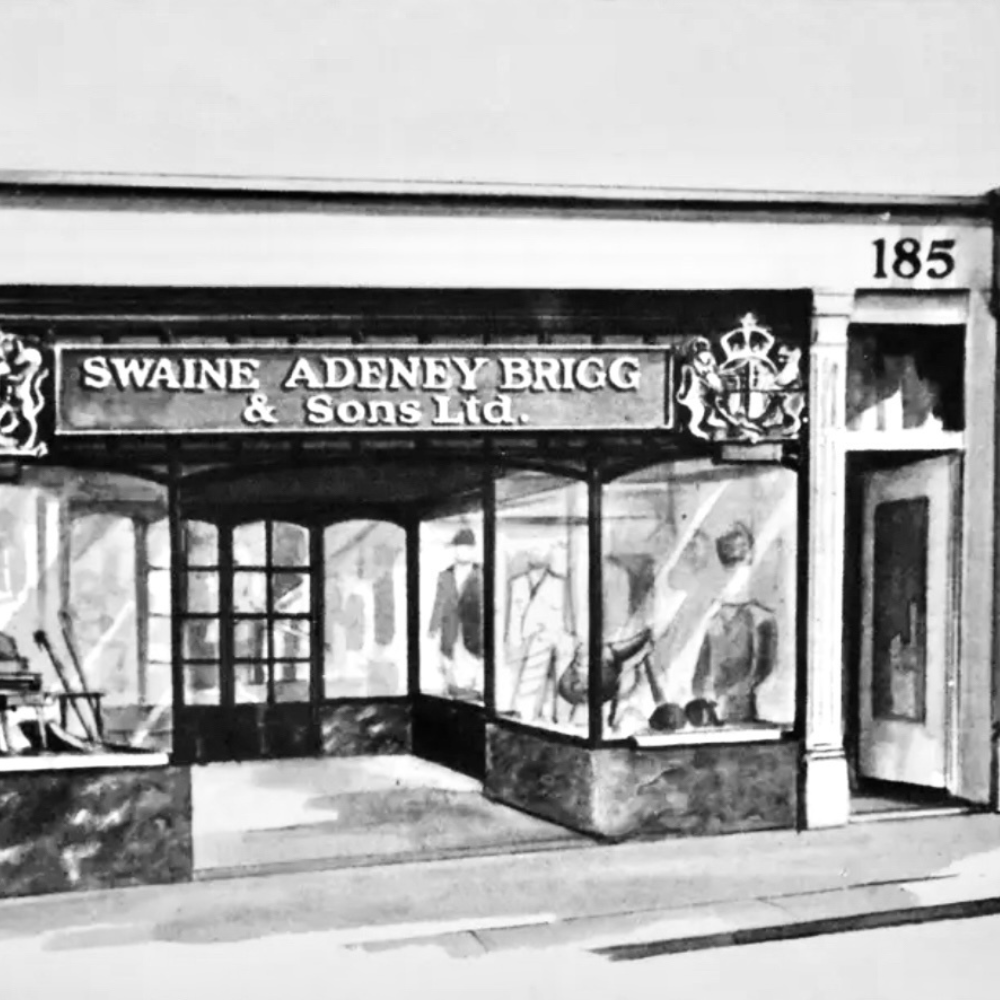

The telling of one’s story is actively encouraged, and as a historic purveyor of luxury goods, Swaine Adeney Brigg actively welcomes piece histories from its clients. With well over 270 years of history to choose from internally, the following historic account marks the close of the silk plush hatting trade, as told by one of the many Master Hatters at Herbert Johnson Mr. David Palmer, one of the great craftsmen of the hatting trade, was regularly given the task of completing hats away from the factories. He had started his working life as a kiln-boy at the turn of the 20th century. He stoked the coke fires to warm the hats for the shapers, with as many as 25 hearing irons nearby. Mr. Palmer would often lean over the shapers and watch how they carried out their work. Fascinated by the process, he became an apprentice in 1907. Each apprentice fell under the care of a “Whimsey Master” who taught him the rudiments of the trade. The boy had himself to pay the craftsman for teaching him, and unfortunately for David, he had no money to pay either for his tuition or to buy the tools he needed. His qualities in those early days must have been apparent as his employer came to his rescue and advanced the money; owing to the way he had watched the shapers beforehand, Mr. Palmer soon picked up the technique. In fact, after only three months of body-making and finishing and after six months shaping, he was told one memorable morning, “Go on your own.”

In his attic at Herbert Johnson’s shop in Bond Street, even though at first sight, the place looked not unlike a particularly untidy potting shed full of hat boxes, he could lay his hand instantly amid the apparent chaos on each and every one of those old tools as he required it. He worked, like those in the different surroundings at Battersby’s had worked; with the absolute unfumbling certainty of the true craftsman, and beneath his expert touch, the hard-felt hood from Stockport, sprang with an extraordinary speed into something that although incomplete, was instantly recognisable as a fashionable bowler hat.

A simple little tool in which a nail formed the essential element then scratched a line at a standard distance around the edge of the hood. Allowing for a wide or a narrower brim, Mr. Palmer cut along this line, moistened the hat’s brim, stretched calico over it, took a hot iron, rubbed it on a greasy pad to make it run more readily and applied it to the outer edge. This outer edge, now temporarily pliable, he turned over quickly and accurately, first at the sides and then at the ends. A cold iron smoothed out such few insubordinate wrinkles as had appeared. He held the embryo in his hand and gazed at it with a critical eye, assuring himself unnecessarily of its absolute symmetry. It was now ready for setting. David placed it in a kind of cradle known as a horse in front of the popping domestic gas fire that acted as a substitute for the coke kiln of his faraway youth, and while the hat was warming to make it pliable, he spoke of the past.

He had been 38 years with one firm. Then, one night during the Second World War, the workshop was destroyed in one of many air raids. But for the fact that he had taken his old tools home with him that evening (though he did not know why: it was not a thing he usually did), they would have been lost with the rest of the building. He took them eventually to Herbert Johnson. The trouble was that the young fellows of the 1950s had no respect for a man’s tools. Instead of putting them back where they found them, they would leave them any-old where. They would fling them down, too, without thinking: although the bench was of wood and the tool was of brass, it was surprising how easily the smooth surface of the metal could become pitted, and once that happened, a hat would be ruined by applying the tool to it. It was a job in which you could not afford to make a mistake, either.

There was no going back. For this particular order, he looked at his instructions. It was for a 6% head, regularly shaped but requiring a slight bulge over the right temple. Selecting a heavy wooden template, known as a standard oval brow, he removed the hat from the horse and eased it while it was still temporarily malleable over the brow. To allow for the slight but distinctive bulge wedges of old cardboard was crudely but effectively forced, at the appropriate spot, between the brow and the malleable felt.

He ran a curling iron along the brim which rose under his hand from its flat, turned-over state to a snaking Edwardian shape, he pared the edge with a light plane to make it absolutely symmetrical, and he sandpapered it so that there should be no roughness to show through the silk ribbon of the binding. With a tool, he had manufactured himself from a ground-down open razor he made smooth, though none would ever see it, the tight underside of the curl.

He had finished. The whole perfect process in which the primitive hood had become a sophisticated hat, ready for the trimming, had taken no more than half an hour. But like all old craftsmen in the hat trade, he kept harking back, perhaps because of the added skill needed for its manufacture, to the great days of the silk hat. He had among the clutter on his bench a piece of plush from an old silk hat:

“Look at it,” he kept saying, “look at the colour of that plush. Nearly as old as I am, that must be. ‘Don’t get plush like that nowadays: it’s all a slaty colour today.”